Stay informed with free updates

Simply sign up to the Fund management myFT Digest — delivered directly to your inbox.

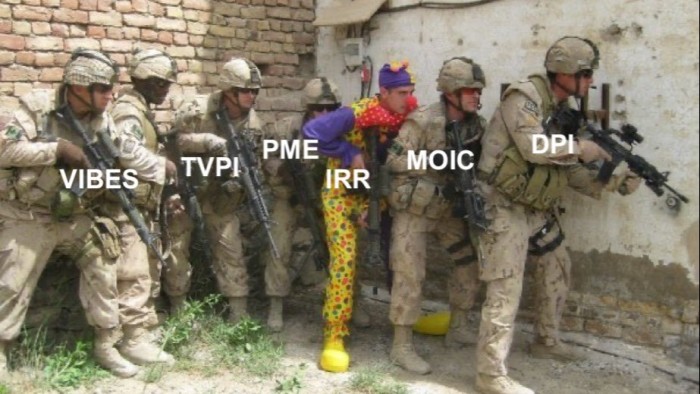

We (should) all know (by now) quite how awful the “internal rate of return” is as a measure of your private equity manager’s long-term performance record. But this hasn’t stopped them bragging.

Ludovic Phalippou, professor of financial economics at the University of Oxford, hammered home the point here on FTAV on why the IRR measure is so pungent:

Early cash flows dominate the calculation, while later ones have almost no impact. You can invest for 40 years, make or lose billions — and your since-inception IRR will still reflect that nice exit in 1980 or whenever.

It’s easy to nod sagely. Sure — some private equity managers may engage in a bit of knowing IRR bait and switch. But if it’s so widely used, IRR must at least have the capacity of being a half-decent measure?

A recent-ish paper by Simon Hayley of Bayes Business School and Onur Sefiloglu of Essex Business School argues not.

The authors investigate annualised internal rate of return measures derived from investor cash flows calculated over varying time horizons. And they find a structural upward bias that they reckon is worth between two to three percentage points per annum.

Two to three percentage points per annum is a lot.

To be clear, this isn’t about PE firms jimmying their numbers with clever NAV loans and well-timed distributions. This is just about maths. The upward bias “arise[s] without any deliberate manipulation by fund managers” and is “inherent in the observable statistical distribution of the cashflows generated by these assets.’”

What’s going on? We’re not going to bore you with the details of the maths on a Monday morning, but it turns out that IRRs will be upwardly biased when two conditions are met.

The first condition is that there must be a high variation of returns for deals with short-term payouts. The second condition is that the deals’ maturity and returns must be in some way related. Think annualised returns from deals that take an age to pay out being reliably lower than returns from deals that pay out quickly.

And what do private equity deal returns look like in practice? Examining 1,585 investment exits by 438 PE firms with acquisition years from 1998 to 2018 Hayley and Sefiloglu draw this pretty chart (zoomable version here):

High variance of short-term deal payouts — aka are the dots on the left all over the place? Check.

A relationship between deal maturity and returns — aka do the dots resemble a giant drop slide? Check.

How much does this pattern of deal returns juice stated IRRs? Again — two to three percentage points per annum. And as Hayley and Sefiloglu observe:

. . . These biases remain poorly understood. As a result, many investors appear to be making substantial allocations to illiquid assets on the basis of biased return measures.

The biggest private equity allocations are made by large, sophisticated institutional investors like sovereign wealth funds, private banks, US university endowments and major pension plans. Unless they’ve been burying their head in the sand for the past two decades we’d hope that this latest reason to be sceptical about IRRs doesn’t come as too much of a shock.

However, it’s unlikely that retail investors have absorbed the full unvarnished IRR canon. And unfortunately, retail investors are currently very much in the sights of wealth managers both the US and the UK.